Latest news: Looking ahead.

2012 steward Marg Whedan photographed the lighthouse as a storm approached.

Hello All,

2020 was the 200th Anniversary of White Island Lighthouse Station (sometimes called Isles of Shoals light). 2020 was also, very likely, the most challenging year in our lifetime.

Due to Covid-19 our lives have been turned upside down and inside out.

We see changes everywhere and White Island is no exception.

Due to the encouragement to social distance, stewards will not be allowed to stay overnight on White Island in 2020. Weather, sea conditions and pandemic issues permitting, possibly in August or September a day trip to the Island can be arranged for volunteers who are willing to perform maintenance tasks. If you are interested, please send me an email. You can then be contacted if the trip materializes.

Two biologists from Shoals Lab will be on island monitoring the tern project, and a construction team should be going out to complete the generator room update which was incomplete at the end of 2019.

Hopefully 2022 brings a return to normalcy for us all and the stewardship program can once again commence. We are accepting applications now for Summer 2022! If you would like more information contact Sue Reynolds at [email protected] or 603-978-2097, or check out our Stewardship page by clicking here.

Additionally, the pandemic has led to the cancellation of both of our annual fundraisers. If you would like to support the ongoing work of Lighthouse Kids, please visit our Donate page.

Thanks to all for your support, and we hope many of you are able to schedule time on the island in 2021.

Sue Reynolds

Lighthouse Kids

2020 was the 200th Anniversary of White Island Lighthouse Station (sometimes called Isles of Shoals light). 2020 was also, very likely, the most challenging year in our lifetime.

Due to Covid-19 our lives have been turned upside down and inside out.

We see changes everywhere and White Island is no exception.

Due to the encouragement to social distance, stewards will not be allowed to stay overnight on White Island in 2020. Weather, sea conditions and pandemic issues permitting, possibly in August or September a day trip to the Island can be arranged for volunteers who are willing to perform maintenance tasks. If you are interested, please send me an email. You can then be contacted if the trip materializes.

Two biologists from Shoals Lab will be on island monitoring the tern project, and a construction team should be going out to complete the generator room update which was incomplete at the end of 2019.

Hopefully 2022 brings a return to normalcy for us all and the stewardship program can once again commence. We are accepting applications now for Summer 2022! If you would like more information contact Sue Reynolds at [email protected] or 603-978-2097, or check out our Stewardship page by clicking here.

Additionally, the pandemic has led to the cancellation of both of our annual fundraisers. If you would like to support the ongoing work of Lighthouse Kids, please visit our Donate page.

Thanks to all for your support, and we hope many of you are able to schedule time on the island in 2021.

Sue Reynolds

Lighthouse Kids

The Keepers of White Island Lighthouse

by Nancy Frye Bergeron

The 200-year-old White Island Lighthouse of the Isles of Shoals along the Maine/New Hampshire coastline began its history in 1820. Lighthouse keepers have played an important role in its history beginning with the first lighthouse keeper in 1821 named Clement Jackson, a local merchant. Many more followed him (see list below).

On July 1, 1939, The United States Coast Guard (USCG) assumed the administration of all the US Lighthouses from the United States Lighthouse Bureau. The existing Lighthouse Bureau lighthouse keepers were given a choice - join the USCG or remain on as civilian lighthouse keepers until their retirement. Most chose to continue on as civilians.

Not much is known about most of the lighthouse keepers but there have been a few whose stories have been shared and documented over time. I have shared a few stories below but highly recommend you visit www.newenglandlighthouses.net a website established by Jeremy D’Entremont in 1997 and current today.

If you are interested in helping save and preserve the White Island Lighthouse at the Isles of Shoals in Rye, New Hampshire contact the Lighthouse Kids organization at

[email protected].

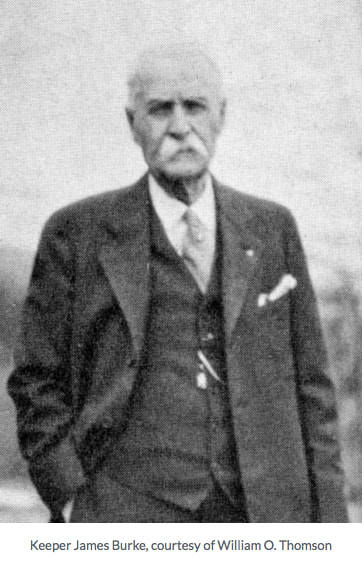

1894-1912 James Burke – James Burke was a Portsmouth native. His is best known for the many rescues he dealt with during his tenure over at the White Island Light. History indicates that the rescues included sixteen women from an overturned boat, three from a similar situation and four sailors found drifting at sea. In 1911, a severe winter storm found Keeper Burke on the island without his assistant Gordon Sullivan and Burke’s wife quite ill with pneumonia. Burke also became ill but as the keeper of the light he felt it was his duty to keep the light lit for those in danger at sea, which he managed to do for six long nights. When Sullivan returned from his leave he contacted Captain Joseph Staples on Appledore Island for help for the Burkes. Staples sent a tugboat from the lifesaving station to carry the Burkes to the mainland for medical assistance. Burke’s bravery and diligence to his role as the keeper of thelight was duly reported in the local newspapers.

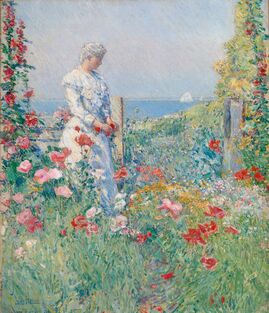

1839-1840 and 1843-1849 Thomas Leighton - Thomas Leighton is probably the most famous

lighthouse keeper of White Island. It was during his first year as the keeper that a severe storm

washed out the wooden walkway between the lighthouse and the keeper's house. The barn

that housed the cow was also destroyed but Leighton managed to save the family cow by

bringing her into the keeper’s house. He was not able to save the Spanish sailors of the brig

Pocahontas who perished when their ship hit the jagged rocks of White Island.

Leighton's famous daughter Celia Thaxter recalled the memory in her poem:

The Wreck of the Pocahontas:

I lit the lamps in the lighthouse tower,

For the sun dropped down and the day was dead.

They shone like a glorious clustered flower,

Ten golden and five red.

Like all the demons loosed at last,

Whistling and shrieking, wild and wide,

The mad wind raged, while strong and fast

Rolled in the rising tide.

The thick storm seemed to break apart

To show us, staggering to her grave,

The fated brig. We had no heart

To look, for naught could save.

The Wreck of the Pocahontas:

I lit the lamps in the lighthouse tower,

For the sun dropped down and the day was dead.

They shone like a glorious clustered flower,

Ten golden and five red.

Like all the demons loosed at last,

Whistling and shrieking, wild and wide,

The mad wind raged, while strong and fast

Rolled in the rising tide.

The thick storm seemed to break apart

To show us, staggering to her grave,

The fated brig. We had no heart

To look, for naught could save.

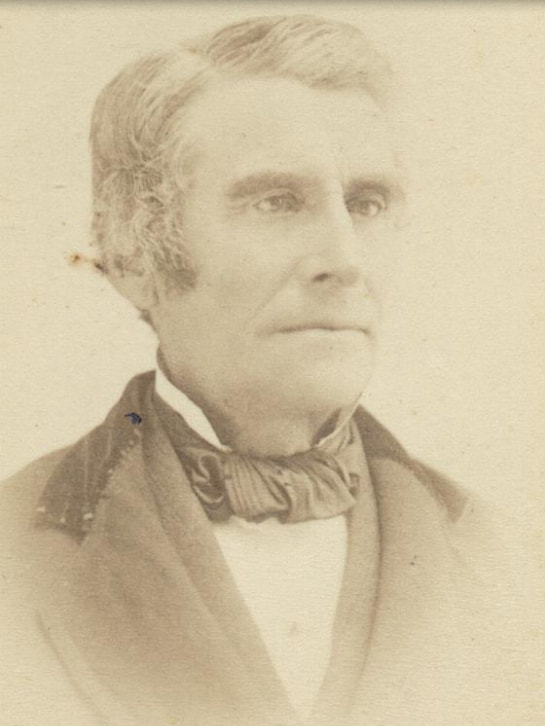

Captain Jonathan Godfrey

Photo courtesy of Hampton Historical Society

Captain Jonathan Godfrey

Photo courtesy of Hampton Historical Society

1849-1855 L.H.D. Shepard – L.H.D. Shepard found it difficult to maintain a garden on the rocky shoreline of White Island. He managed to grow onions, squashes, cabbages and turnips as noted in an observation written by Nathaniel Hawthorne after visiting the colorful keeper in September of 1852. Hawthorne also mentions that Keeper Shepard “does not bear a very high character among his neighbors.” During Shepard’s tenure as the keeper on White Island he managed to lose two wives. His first wife, very young and overwhelmed by the desolation and the solitude of being left too many times alone by her husband, passed away. His second wife chose to leave him on his island and return to her family on the mainland.

1855: Temporary Lighthouse Keeper John Bragg Downs - John Braggs Downs was a member of the Downs family, a family that had been living at the Isles of Shoals for many generations.Downs frequently visited White Island to visit the keepers and acquired knowledge of many of the keeper duties. When he was asked to take on the Lighthouse Keeper position on a temporary basis, while the new Keeper Richard Haley went ashore to bring his family over to White Island, he agreed. During his stay on White Island a severe winter storm blew in, causing him to shelter in the keeper's house until the storm passed. The Captain of a Russian brig did not see the lighthouse beam in the storm and his ship crashed into the rocks on the island where it became wedged. During a lull in the storm the Captain could see how close the ship was to the lighthouse so, in fear that he and his men would succumb to the pounding and freezing waves, he asked for a volunteer to go for assistance. One of his sailors agreed to fight his way to the keeper's house. It was a startled Downs and his assistant who opened the door to

find the exhausted and bruised Russian sailor. Help was needed for the remaining fourteen

sailors so John and his assistant made their way to the ship and used a line from ship to the

shore to guide the men to safety. Downs had to use his own body as an anchor for the line. All

fourteen sailors made it and welcomed the warmth and food offered at the keeper's house.

1861-1863 Assistant Lighthouse Keeper Jonathan Godfrey – Jonathan Godfrey, fondly known as

Jonty, served as an assistant Lighthouse Keeper under Keeper Alfred J. Leavitt during the Civil

War. He was a local farmer as well as the owner and ship captain of the vessel Black Hawk that

transported lumber and salt from Hampton, New Hampshire to Boston, Massachusetts. His wife

Theodate Hobbs, shared the same name as her mother-in-law, Theodate Godfrey. Godfrey and

Theodate had fifteen children together, all who survived to adulthood except one.

1855: Temporary Lighthouse Keeper John Bragg Downs - John Braggs Downs was a member of the Downs family, a family that had been living at the Isles of Shoals for many generations.Downs frequently visited White Island to visit the keepers and acquired knowledge of many of the keeper duties. When he was asked to take on the Lighthouse Keeper position on a temporary basis, while the new Keeper Richard Haley went ashore to bring his family over to White Island, he agreed. During his stay on White Island a severe winter storm blew in, causing him to shelter in the keeper's house until the storm passed. The Captain of a Russian brig did not see the lighthouse beam in the storm and his ship crashed into the rocks on the island where it became wedged. During a lull in the storm the Captain could see how close the ship was to the lighthouse so, in fear that he and his men would succumb to the pounding and freezing waves, he asked for a volunteer to go for assistance. One of his sailors agreed to fight his way to the keeper's house. It was a startled Downs and his assistant who opened the door to

find the exhausted and bruised Russian sailor. Help was needed for the remaining fourteen

sailors so John and his assistant made their way to the ship and used a line from ship to the

shore to guide the men to safety. Downs had to use his own body as an anchor for the line. All

fourteen sailors made it and welcomed the warmth and food offered at the keeper's house.

1861-1863 Assistant Lighthouse Keeper Jonathan Godfrey – Jonathan Godfrey, fondly known as

Jonty, served as an assistant Lighthouse Keeper under Keeper Alfred J. Leavitt during the Civil

War. He was a local farmer as well as the owner and ship captain of the vessel Black Hawk that

transported lumber and salt from Hampton, New Hampshire to Boston, Massachusetts. His wife

Theodate Hobbs, shared the same name as her mother-in-law, Theodate Godfrey. Godfrey and

Theodate had fifteen children together, all who survived to adulthood except one.

White Island Lighthouse Keepers

1821-1824 Clement Jackson

1824-1829 Benjamin Haley

1829 William Godfrey

1829-1839 Joseph L. Locke

1839-1841 Thomas Leighton

1841-1843 Joseph Cheever

1843-1849 Thomas Leighton

1849-1853 L.H.D. Shepard

1853-1861 Richard G. Haley

1861-1866 Alfred J. Leavitt

1866-1869 Alonzo Wise

1869 Joshua Bickford

1869-1874 Jonathan W. Berry

1874-1876 Israel R. Miller

1876-1880 Edwin J. Hobbs

1880-1894 David R. Grogan

1894-1912 James Burke

1912-1913 Jerome C. Brown

1915-1921 Joseph H. Upton

1922-1926 John H. Upton

1926-1930 Albert Staples

1930-1935 John H. Olsen

1936-1941 Wilbur I. Brewster

1939 On July 1, 1939, the United States Coast Guard (USCG) assumed the

administration of all the US Lighthouses from the United States Lighthouse

Bureau.

1986 Aids to navigation at the White Island Lighthouse where automated in 1986,

however the USCG still maintains the light and fog horn as active aids to

navigation.

Bibliography

D’Entremont, Jeremy. “New England Lighthouses: A Virtual Guide”. Available online at

newenglandlighthouses.net.

D’Entremont, Jeremy. “White Island Light”. Available online at seacoastnh.com.

Anderson, Kraig. “Isles of Shoals (White Island) Lighthouse”. Available online at

lighthousefriends.com.

Hunts, James K. ‘Captain Jonathan Godfrey”. Available online at Hampton.lib.nh.us

1821-1824 Clement Jackson

1824-1829 Benjamin Haley

1829 William Godfrey

1829-1839 Joseph L. Locke

1839-1841 Thomas Leighton

1841-1843 Joseph Cheever

1843-1849 Thomas Leighton

1849-1853 L.H.D. Shepard

1853-1861 Richard G. Haley

1861-1866 Alfred J. Leavitt

1866-1869 Alonzo Wise

1869 Joshua Bickford

1869-1874 Jonathan W. Berry

1874-1876 Israel R. Miller

1876-1880 Edwin J. Hobbs

1880-1894 David R. Grogan

1894-1912 James Burke

1912-1913 Jerome C. Brown

1915-1921 Joseph H. Upton

1922-1926 John H. Upton

1926-1930 Albert Staples

1930-1935 John H. Olsen

1936-1941 Wilbur I. Brewster

1939 On July 1, 1939, the United States Coast Guard (USCG) assumed the

administration of all the US Lighthouses from the United States Lighthouse

Bureau.

1986 Aids to navigation at the White Island Lighthouse where automated in 1986,

however the USCG still maintains the light and fog horn as active aids to

navigation.

Bibliography

D’Entremont, Jeremy. “New England Lighthouses: A Virtual Guide”. Available online at

newenglandlighthouses.net.

D’Entremont, Jeremy. “White Island Light”. Available online at seacoastnh.com.

Anderson, Kraig. “Isles of Shoals (White Island) Lighthouse”. Available online at

lighthousefriends.com.

Hunts, James K. ‘Captain Jonathan Godfrey”. Available online at Hampton.lib.nh.us

White Island Lighthouse Station is an icon of New Hampshire’s Maritime History and an Active Aide to Navigation for 200 years!!!

1950- Top of the tower at White Island Lighthouse.

A LOOK BACK IN TIME

White Island Lighthouse Station 1946-1948

Written by: Susan Reynolds, Lighthouse Kids

References: An unpublished Memoir by George O. Tolman and The Shoreliner Magazine, September 1950, provide a window to a time past on White Island.

“Since 1820 White Island Lighthouse has been a welcome sight to those who love the sea.”

(The Shoreliner)

In 1939 the Coast Guard had taken over lighthouse keeping from the Lighthouse Service.

As World War II concluded and service men were released to civilian life, the United States Coast Guard desperately needed new recruits. Due to the shortage of qualified keepers, civilians who had been keepers for the Lighthouse Service could remain in service with a choice of joining the Coast Guard or continuing as civilians.

On White Island five men were stationed as keepers. Lighthouse Keeper, Douglas Larrabee and his assistant Lester Davis, were civilians, stationed at White Island, living in the larger of the two keepers’ houses on the island, a Victorian duplex. Doug and Lester were both married men whose wives visited occasionally. Doug had a teenage son who came to stay in the summer months and enjoyed sharing the light keeping duties. The smaller cottage housed three Coast Guardsmen. All five adults had equal duties. Each had one week’s liberty every five weeks.

The two houses on White Island were situated about 15 feet above the water, protected somewhat by a headland to seaward, and facing three mainland states - Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. The living facilities on White Island lacked electricity, running water and indoor plumbing which were available at most lighthouse stations at the time. The tool shed and boathouse stood about 10 feet above the water.

August 1946, at seventeen years of age, George Tolman, with his parents to sign his enlistment papers, was sworn in and inducted into the United State Coast Guard at the First District Headquarters, Boston Massachusetts.

There was to be no bootcamp for George or the one other inductee that day, Norm Barrett; rather, for on the job training they were shipped to Portland Maine and stationed at Biddeford Pool. Subsequently, more training in boat handling and standing watches at Wood Island Life Saving Station, a short boat ride from Kittery Point Maine and Frisbee’s General Store. George rose through the Coast Guard ranks exceptionally fast, and was promoted to Seamen First Class, a requisite for transfer to his first permanent assignment at White Island Lighthouse and Look-out Station at the Isles of Shoals.

On a chilly December 1946 morning, training in boat handling and standing watches complete, George hopped aboard the 36’ motor lifeboat, with Willard Orr, Chief Boatswain’s mate at the wheel and Norm as crew, the 3 headed offshore. The Coast Guard lifeboats were wet and slow but dependable. If rolled and swamped, they self-righted dumping the sea water back into the ocean, thus unsinkable! The trip to White Island, was wet and uncomfortable, but secure.

Six miles offshore and nine miles from Wood Island, the southernmost island at the Isles of Shoals, White Island beckoned George ashore. Chief Orr waited about 100 feet from shore in the motor lifeboat with George and supplies to be offloaded. With white water visible, the landing appeared treacherous. Keeper, Doug Larrabee, with one crew hopped aboard a 16’ double ended boat as it proceeded to slide down the greased marine railway, enter the water and head skillfully toward the lifeboat. Pulling up alongside, Doug offered his hand in a friendly welcome and George responded by introducing himself. The crew, a discharged Coast Guardsman, warmly bid farewell to Doug for the last time and exchanged places with George, who cautiously climbed aboard the pitching peapod. After the island supplies were transferred to the peapod, Doug engaged the engine and headed for shore.

The trip into the island took more time and tactical skill. While waiting for a lull in the wave action Doug explained island life. As a calm window approached, Doug quickly motored toward the island. When close, he shut down the engine, stood in the stern of the boat and facing forward expertly rowed onto the greased rails, where a waiting seaman secured a cable to the bow of the boat, signaled a second man in the boathouse to throw the diesel into gear. The peapod, crew and supplies easily moved up the greased rail, onto the boathouse platform and out of the seas reach.

Doug, George, supplies and gear were offloaded. Doug immediately barked out orders, directing everyone to store the arriving provisions in the appropriate quarters. Then all were ordered to gather in Doug’s kitchen for proper introductions and a discussion of island operations. Doug was the largest person in the group with an authoritative, booming voice but obviously respected and liked by his crew. In short order George felt comfortable and at home!

Watches on the island consisted of four hours on duty, then eight hours off. Keeping the light, foghorn and look-out wasn’t a simple task. A triangular covered walkway not only provided protection from the elements but also bridged a large granite crevice often awash with seawater. This same crevice was a superior site for the outhouse as the ocean regularly swept it clean! The walkway sloped upward from the backyard, leading to the compressor room that housed foghorn equipment including diesels to run the foghorn which was just outside at the base of the tower. Entry to the tower was from the compressor room. Within the tower, a rod-iron spiral staircase led to the top and the large number two order Fresnel lens that sat on a circular metal rotating base. Every four hours when the light was in use (reduced visibility, night, fog or storm) heavy weights suspended on cables within the tower walls needed to be cranked up by the crewman on duty. to slowly lower, causing the prismatic lens to rotate. It worked the same as a weight operated clock mechanism. For identification by mariners, the timing of the rotation produced a characteristic specific to White Island. The kerosene light was problematic. It required at least twenty minutes preheating with an alcohol flame. The oil light would occasionally cool, thus requiring constant vigilance to prevent a smoke and soot from clouding the area. Standing 82 feet above high water, on a clear night, the 60,000 candlepower light could be seen for fifteen miles.

In addition to keeping the light and foghorn operational, White Island was also designated as a lookout station. Insuring station integrity required round the clock watches. When a vessel in trouble was spotted radio contact between vessel, Portsmouth Harbor Station and White Island was maintained. A rescue boat would be sent out from Portsmouth Station and/or in extreme emergencies the 25 footer stored in the boathouse could be launched down the greased railway to provide assistance.

George quickly learned that there were lots of duties to keep the crew busy. But there was also lots of fun. Doug usually tried to have party night once a week in calm weather when duties were light. Contained in the weekly supplies were five jugs of Gibley’s gin. Always hidden from Lester, who was quiet and reserved most of the week, until party night and his first glass of gin was drained.

Late in the fall when a blustery wind blew and the sea piped up, Chief Orr from Wood Island refused to bring the 36’ motor lifeboat out with the White Island provisions, declaring it was too rough. Keeper, Doug Larrabee, disagreed and decided that they would go in and get their own supplies from Frisbee’s store; plus, they could manage the crew rotation on their own! Doug ordered George to grab a compass, extra gas and anything else he could think of. The 25’ self-bailing boat was launched from the boathouse, down the rails and into the water. Nine miles and 90 minutes later, the crew of three passed Portsmouth Harbor Station and headed into Frisbee’s wharf where the boxes of provisions and the returning crewmember waited. With crew exchanged and supplies packed they headed back out. The return trip was wet and rough but uneventful until the fog rolled in a couple of miles short of White Island. Luckily Lester had started the foghorn so that George could get a compass bearing on the sound. Navigation and seamanship were exceptional. Doug landed right on the rails; George hopped out and secured the cable to the bow-eye and Lester engaged the diesel. They were back home and as soon as they could stow everything, IT WAS PARTY TIME!

White Island Lighthouse Station 1946-1948

Written by: Susan Reynolds, Lighthouse Kids

References: An unpublished Memoir by George O. Tolman and The Shoreliner Magazine, September 1950, provide a window to a time past on White Island.

“Since 1820 White Island Lighthouse has been a welcome sight to those who love the sea.”

(The Shoreliner)

In 1939 the Coast Guard had taken over lighthouse keeping from the Lighthouse Service.

As World War II concluded and service men were released to civilian life, the United States Coast Guard desperately needed new recruits. Due to the shortage of qualified keepers, civilians who had been keepers for the Lighthouse Service could remain in service with a choice of joining the Coast Guard or continuing as civilians.

On White Island five men were stationed as keepers. Lighthouse Keeper, Douglas Larrabee and his assistant Lester Davis, were civilians, stationed at White Island, living in the larger of the two keepers’ houses on the island, a Victorian duplex. Doug and Lester were both married men whose wives visited occasionally. Doug had a teenage son who came to stay in the summer months and enjoyed sharing the light keeping duties. The smaller cottage housed three Coast Guardsmen. All five adults had equal duties. Each had one week’s liberty every five weeks.

The two houses on White Island were situated about 15 feet above the water, protected somewhat by a headland to seaward, and facing three mainland states - Maine, New Hampshire and Massachusetts. The living facilities on White Island lacked electricity, running water and indoor plumbing which were available at most lighthouse stations at the time. The tool shed and boathouse stood about 10 feet above the water.

August 1946, at seventeen years of age, George Tolman, with his parents to sign his enlistment papers, was sworn in and inducted into the United State Coast Guard at the First District Headquarters, Boston Massachusetts.

There was to be no bootcamp for George or the one other inductee that day, Norm Barrett; rather, for on the job training they were shipped to Portland Maine and stationed at Biddeford Pool. Subsequently, more training in boat handling and standing watches at Wood Island Life Saving Station, a short boat ride from Kittery Point Maine and Frisbee’s General Store. George rose through the Coast Guard ranks exceptionally fast, and was promoted to Seamen First Class, a requisite for transfer to his first permanent assignment at White Island Lighthouse and Look-out Station at the Isles of Shoals.

On a chilly December 1946 morning, training in boat handling and standing watches complete, George hopped aboard the 36’ motor lifeboat, with Willard Orr, Chief Boatswain’s mate at the wheel and Norm as crew, the 3 headed offshore. The Coast Guard lifeboats were wet and slow but dependable. If rolled and swamped, they self-righted dumping the sea water back into the ocean, thus unsinkable! The trip to White Island, was wet and uncomfortable, but secure.

Six miles offshore and nine miles from Wood Island, the southernmost island at the Isles of Shoals, White Island beckoned George ashore. Chief Orr waited about 100 feet from shore in the motor lifeboat with George and supplies to be offloaded. With white water visible, the landing appeared treacherous. Keeper, Doug Larrabee, with one crew hopped aboard a 16’ double ended boat as it proceeded to slide down the greased marine railway, enter the water and head skillfully toward the lifeboat. Pulling up alongside, Doug offered his hand in a friendly welcome and George responded by introducing himself. The crew, a discharged Coast Guardsman, warmly bid farewell to Doug for the last time and exchanged places with George, who cautiously climbed aboard the pitching peapod. After the island supplies were transferred to the peapod, Doug engaged the engine and headed for shore.

The trip into the island took more time and tactical skill. While waiting for a lull in the wave action Doug explained island life. As a calm window approached, Doug quickly motored toward the island. When close, he shut down the engine, stood in the stern of the boat and facing forward expertly rowed onto the greased rails, where a waiting seaman secured a cable to the bow of the boat, signaled a second man in the boathouse to throw the diesel into gear. The peapod, crew and supplies easily moved up the greased rail, onto the boathouse platform and out of the seas reach.

Doug, George, supplies and gear were offloaded. Doug immediately barked out orders, directing everyone to store the arriving provisions in the appropriate quarters. Then all were ordered to gather in Doug’s kitchen for proper introductions and a discussion of island operations. Doug was the largest person in the group with an authoritative, booming voice but obviously respected and liked by his crew. In short order George felt comfortable and at home!

Watches on the island consisted of four hours on duty, then eight hours off. Keeping the light, foghorn and look-out wasn’t a simple task. A triangular covered walkway not only provided protection from the elements but also bridged a large granite crevice often awash with seawater. This same crevice was a superior site for the outhouse as the ocean regularly swept it clean! The walkway sloped upward from the backyard, leading to the compressor room that housed foghorn equipment including diesels to run the foghorn which was just outside at the base of the tower. Entry to the tower was from the compressor room. Within the tower, a rod-iron spiral staircase led to the top and the large number two order Fresnel lens that sat on a circular metal rotating base. Every four hours when the light was in use (reduced visibility, night, fog or storm) heavy weights suspended on cables within the tower walls needed to be cranked up by the crewman on duty. to slowly lower, causing the prismatic lens to rotate. It worked the same as a weight operated clock mechanism. For identification by mariners, the timing of the rotation produced a characteristic specific to White Island. The kerosene light was problematic. It required at least twenty minutes preheating with an alcohol flame. The oil light would occasionally cool, thus requiring constant vigilance to prevent a smoke and soot from clouding the area. Standing 82 feet above high water, on a clear night, the 60,000 candlepower light could be seen for fifteen miles.

In addition to keeping the light and foghorn operational, White Island was also designated as a lookout station. Insuring station integrity required round the clock watches. When a vessel in trouble was spotted radio contact between vessel, Portsmouth Harbor Station and White Island was maintained. A rescue boat would be sent out from Portsmouth Station and/or in extreme emergencies the 25 footer stored in the boathouse could be launched down the greased railway to provide assistance.

George quickly learned that there were lots of duties to keep the crew busy. But there was also lots of fun. Doug usually tried to have party night once a week in calm weather when duties were light. Contained in the weekly supplies were five jugs of Gibley’s gin. Always hidden from Lester, who was quiet and reserved most of the week, until party night and his first glass of gin was drained.

Late in the fall when a blustery wind blew and the sea piped up, Chief Orr from Wood Island refused to bring the 36’ motor lifeboat out with the White Island provisions, declaring it was too rough. Keeper, Doug Larrabee, disagreed and decided that they would go in and get their own supplies from Frisbee’s store; plus, they could manage the crew rotation on their own! Doug ordered George to grab a compass, extra gas and anything else he could think of. The 25’ self-bailing boat was launched from the boathouse, down the rails and into the water. Nine miles and 90 minutes later, the crew of three passed Portsmouth Harbor Station and headed into Frisbee’s wharf where the boxes of provisions and the returning crewmember waited. With crew exchanged and supplies packed they headed back out. The return trip was wet and rough but uneventful until the fog rolled in a couple of miles short of White Island. Luckily Lester had started the foghorn so that George could get a compass bearing on the sound. Navigation and seamanship were exceptional. Doug landed right on the rails; George hopped out and secured the cable to the bow-eye and Lester engaged the diesel. They were back home and as soon as they could stow everything, IT WAS PARTY TIME!

“White Island – an exceptional place with few luxuries had infrastructure that made our living an old-time experience with boat activity unequalled – whether on calm or rough seas. Between Memorial Day and Labor Day, a daily ferry, the Kaboko, served the area. It made round trips from Portsmouth to Star Island, a home for religious conventions, summer residences as well as a large hotel. Even some of the smaller islands became lightly inhabited during the summer.The Isles of Shoals and particularly White Island remained remote from the mainland humdrum. Life for sixteen months – unique.” (Tolman)

References: George O. Toleman, Atlantic Watch U.S. Coast Guard Later Forties, A Memoir 1946-49, Unpublished, May 20, 2002.

Chester P. Hartford, White Island Light, The Shoreliner Home-Town Magazine of the Seacoast, Portsmouth N.H., Herbert F. Georges, 1950, pages 20-23.

References: George O. Toleman, Atlantic Watch U.S. Coast Guard Later Forties, A Memoir 1946-49, Unpublished, May 20, 2002.

Chester P. Hartford, White Island Light, The Shoreliner Home-Town Magazine of the Seacoast, Portsmouth N.H., Herbert F. Georges, 1950, pages 20-23.

The Lighthouse Kids - Helping Save A Piece of History

White Island Lighthouse Station is a historical landmark from New England's past and a pillar of light protecting northeastern mariners. It's also New Hampshire's only offshore lighthouse. Did you know that this magnificent white brick tower has recently been repaired, but the lighthouse station is still in grave danger?

Mission of Lighthouse Kids Incorporated

Lighthouse Kids Incorporated is a group of Seacoast New Hampshire students, alumni, interested members of the community and the organization's Board of Directors. Together we share a mission to save and maintain the White Island Lighthouse Station at the Isles of Shoals through service learning projects and volunteer efforts. The goal of Lighthouse Kids' is to return White Island in Rye, N.H. to the majestic beauty it was known for at the turn of the 19th century.

We plan to do this by fundraising, raising awareness and creating partnerships with all parties interested in saving and maintaining White Island Light Station.

Lighthouse Kids strives to increase opportunities for the public to participate in White Island Lighthouse preservation and to expand public access, enabling all to experience the wonder of the island. We would like to see White Island Station's blessings secured for future generations.

White Island Lighthouse Station is a historical landmark from New England's past and a pillar of light protecting northeastern mariners. It's also New Hampshire's only offshore lighthouse. Did you know that this magnificent white brick tower has recently been repaired, but the lighthouse station is still in grave danger?

Mission of Lighthouse Kids Incorporated

Lighthouse Kids Incorporated is a group of Seacoast New Hampshire students, alumni, interested members of the community and the organization's Board of Directors. Together we share a mission to save and maintain the White Island Lighthouse Station at the Isles of Shoals through service learning projects and volunteer efforts. The goal of Lighthouse Kids' is to return White Island in Rye, N.H. to the majestic beauty it was known for at the turn of the 19th century.

We plan to do this by fundraising, raising awareness and creating partnerships with all parties interested in saving and maintaining White Island Light Station.

Lighthouse Kids strives to increase opportunities for the public to participate in White Island Lighthouse preservation and to expand public access, enabling all to experience the wonder of the island. We would like to see White Island Station's blessings secured for future generations.

Click to set custom HTML

Click to set custom HTML

Take a sunset boat cruise to White Island and help preserve the Lighthouse. (Denise J. Wheeler photo)

Take a sunset boat cruise to White Island and help preserve the Lighthouse. (Denise J. Wheeler photo)